vol. 8 - The Tribe

The Tribe (2014)

directed by Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

Rose Pacult

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

When I first got to boarding school I remember needing to have my student ID taken at a building about a mile from my dorm. I got totally lost. My new shoes left blisters. I ended up barefoot, hitching a ride with strangers on an offbeat road outside Detroit, learning I’d walked five miles opposite where I needed to go, and eventually, much later, stoned and missing the whole day of class, being brought to the right spot. There, I smiled for the portrait. Sweaty, bruised, raw-footed. But there, at last.

The worst beginning imaginable to going to a school hundreds of miles away from home, I thought. In under three hours, Ukrainian filmmaker Myroslav Mykhailovych Slaboshpytskyi’s debut film The Tribe revokes my complaints. Premiering at Cannes in 2014, The Tribe follows a new student at a school for the deaf. The film doesn’t need translations, nor does it provide any. Mostly silent, the scenes collide into each other and overwhelm with statements on inequality, touching on education, geo-politics, sex work, poverty, abortion, and crime. Not a word is spoken out loud.

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

This is a film about high schoolers, a drama, and a damn well-made commentary on what happens when the powerful use their position to weaken the people and their right to live safely, but it is never the case. I love this subset of the high school film genre—boarding school movies involving romance. I look out for storylines with queer romances where the stories go wrong. Here, there’s none of that gayness. Instead, romance goes wrong when love between two heterosexual students suffers a tragedy at the hands of those in charge, ultimately leading to serial murders.

There’s this overwhelming loudness to what flashes on screen, beginning as soon as the main student arrives by bus in the town of his new school. Lost, he asks for directions. He walks through a park, into a brick building, watches a May Day celebration, and a teacher directs him to his dorm room. Before getting there, the students take him, force him to unrobe, make sure he isn’t concealing anything, then promptly mug him. He’s sent to the wrong room. A very bleak welcome, for sure.

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

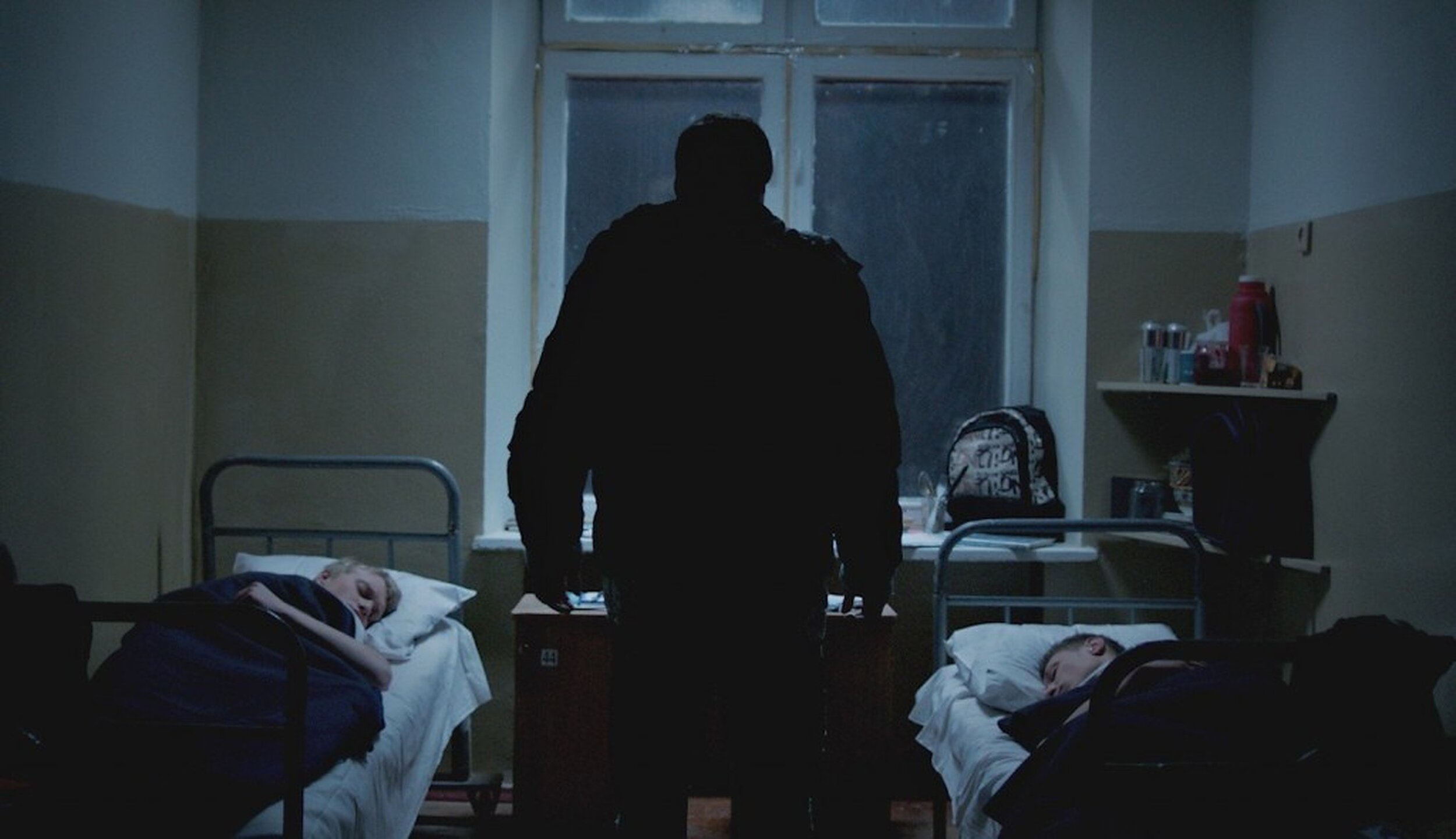

When he does arrive at the right room, he’s beaten. The film shows boarding school experiences in a small town located at the intersection of Ukrainian highways. Truckers often pass through and spend the night. Without translations, subtitles, or spoken language, the interpretation of what’s going on relies heavily on focusing scene to scene on what’s happening on screen: the blue-grey hues in combination with the quick passing of a light mood at the May Day festivities, to the unnamed protagonist becoming a pimp to two of the female students and later murdering his peers who act malevolently (under order from their teachers)—there is a certain demand to understand the bleakness of the film, and of what can happen when money is low and students come together under very difficult circumstances. How did things escalate so quickly? I ask myself while watching for the sixth time.

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

The plot emerges as prostitution offers a way to finance the fundamental need for food. Going back to my early days at boarding school, I remember a late night when I went out with a senior who owned a car. We drove downtown to Detroit to buy drugs. I sat in the Jeep while waiting for the senior guy to score an ounce of pot for us to deal and to enjoy. While waiting in the empty vehicle for the deal to go down with a smaller car, I heard a tap tap on my window. One of the dealers had left the car and come to my window. Surprising me, I rolled down the window and he said, “I want you to know, that guy you’re with, we aren’t messing with him anymore. He just offered you up to us in exchange for the green. We don’t need pussy. We need money.”

I remember sitting in silence on the ride back to campus. Feeling hurt, not saying a word, and wanting to tell him he was a bad dude. Never mentioning that late night. We had food then, shelter, a place to call home that was safe. I never experienced what those in the film felt: early on, the need for food overwhelms—as a scene cuts to a dark park with a few of the students mugging someone for groceries. The school doesn’t have enough to feed them. Outside of shelter, they’re on their own. A particularly quick yet impactful scene shows the school head with a fellow administrator at a desk having their lunch—a nice selection of cheeses and wines, bread and fruits. Later, a teacher rapes a student. This is not the only rape in the film. Can the sex work be legal, given how young the students are? Even after watching many times, I’m unsure of the girls’ ages and how to answer the question. At a truck stop, a girl is banging against a dashboard while the new student, acting as a broker for sex and money, lights a smoke in the parking lot.

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

The new student falls in love with one of the girls he’s protecting, and when she becomes pregnant, he robs a teacher’s house, finding a fortune, enough for both the back-alley abortion, and passports with visas to Italy for the girls.

Imagine a world where that medicine isn’t available, the pain of a back-alley abortion, the lengths to secure funds, and then where the passports to leave such a place, for the girls who undergo such pain, are destroyed. After a rape, an abortion, starvation, and then chance at freedom is removed, so vanishes the hope. What would happen to the emotions of those involved? The powerful—the teachers—left unchecked, rely on the second in command, a group of students who receive benefits for their handiwork, count on them to handle the revenge of the robbery of the teacher’s house, and do ultimately destroy the passports, along with bashing in the head of the guilty thief.

The Tribe | 2014 | dir. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi

Power imbalances when left uncheck result in circumstances like what is seen at the end of this film. Without reiterating the end, I will leave you with asking, what around you is imbalanced and how are you in the chain of command? What can we do to change that which is unjust? Sure, The Tribe is a high school movie, but it is also a damn fine social commentary on equality. A high school drama with enough pain and juicy scenes of sex, love, and brutality to keep you coming back to questions we can ask about our own lives as much as the lives of these students.

Rose Pacult is an activist, artist, and performer presenting in over ten countries, as well as an author of several publications. Her latest authored/co-authored art & prose & poetry books include Slapstick Formalism, ICH LERNE SCHREIBEN („Schreiben mit Jungpionier Espinosa”), TALISMAN, Lifter+Lighter, and Knowing Zasd by His Walk. She has a new book coming out with Markus Butkereit this fall on tornadoes and Rube Goldberg machines from Possible Books.