vol. 28 - Good Will Hunting

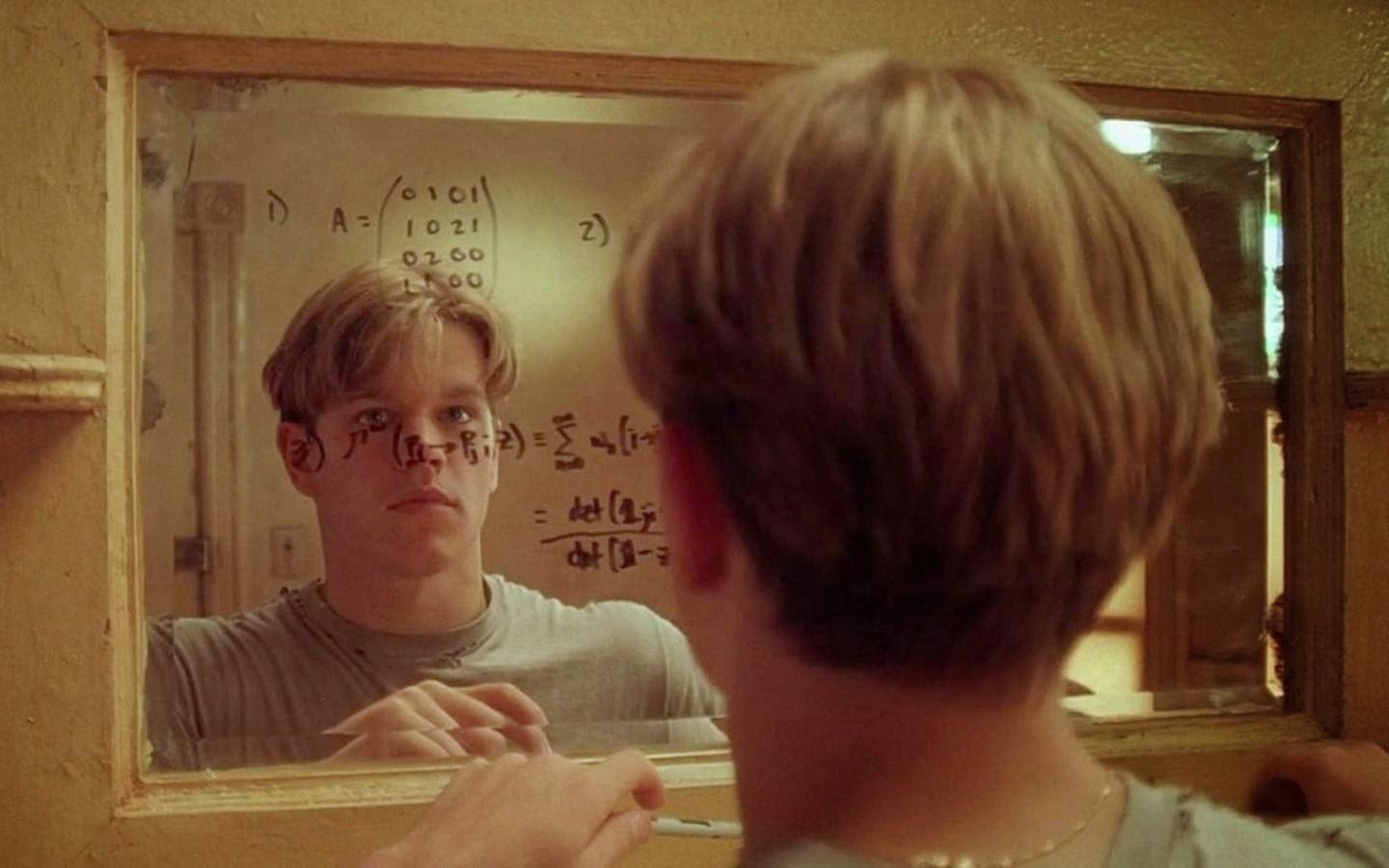

Good Will Hunting (1997)

directed by Gus Van Sant

Christopher Bowen

Good Will Hunting | 1997 | dir. Gus Van Sant

The summer of 1998, two years before I left for college, would start a journey that would change me and my life indefinitely.

When I watched Good Will Hunting the summer after high school ended, I and a girl that I was dating at the time thought it would be a good date movie. Later that summer, she would go back to her university and I would start at mine. We both knew this. She wrote me a letter that August about life and how much her experience with me that summer meant to her. I kept it for some years, but never saw her again.

You have to consider the context of the late nineties: around this time, I was young like the main character, Will, impressionable and in some ways cocky. I honestly used to think I could live forever, that I was partially infallible. And though I wasn't as much of a smartass as the main character of Good Will Hunting, my confidence in myself shot up after high school.

I used to think I was a tough kid, too. Tough enough, I guess. I worked construction for two summers in college and later published a short story about being a mason tender with migrant workers long afterwards.

When my life was interrupted in 2000 and I was hospitalized for manic depression, I found myself cut off from any planning of a future. I had to deal with the present. I was hearing voices sometimes and had lost touch with some reality. My father and mother were afraid it was schizophrenia. The psychiatrist thought it was a deep, manic episode that hadn’t been resolved or addressed. I was locked in with a buzzer at the end of the ward floor staring every night into the deep dark of a ninth story Cleveland hospital window.

I would watch street lights and gas rise from sewers at night like ghosts, or strip the bed and mess the sheets up to make them think I had been sleeping. They tried medications on me and I drooled sometimes. I tried to read books, but couldn’t focus. They wouldn’t even allow me razors for shaving. Sometimes, I prayed. I had been too strong for too long and needed help.

For someone who was once diagnosed and hospitalized with depression, I find it specifically hard to swallow that the late, great Robin Williams committed suicide. I find it especially hard to swallow that he did because to me, Robin Williams will have no better role than this movie. The way he shows us the wisdom of having lived a full life is rare. It is something only time can give a person, how someone looks back on regrets and uses them to form true character.

Was he really acting?

Ben Affleck and Matt Damon, who co-wrote the script for Good Will Hunting in 1994, won an Academy Award for the movie, as did Robin Williams for Best Supporting Actor. The storytelling is great, the characters and acting well-developed. Above the drama of the movie, its evolving characters and plotlines, I truly believe the park scene can sum up a lot of climaxes in the story. It’s the beginning of the friendship between Will (Damon) and Sean (Williams.) And although this takes place maybe a quarter into the film, their conversation here (or lack thereof) really denotes an emotional falling out in the two’s relationship: a humbling of Will and the strength, wit, and charisma of Sean.

So, when did Robin Williams need help before dying? I have been there: the monthly counselor check-ins, the prescription refills. Empty bottles and unknown futures leaving a hospital or diagnosis—we don’t have to be the superhero of our own story, and that's maybe the point of this essay.

I spoke on the hospital landline with my then-girlfriend once or twice during my six-to-eight-week stay and I say that nonchalantly like it was a vacation at the Radisson. She never knew of the changes going on with me there, and eventually I lost her through the whole damn process.

During the day, I went to occupational group therapy with other patients: here, bake some cookies. Here, learn to cope with this disease. One day, you may be free. You will be whole like the cookie.

In retrospect, I think about my own experience with suicide and depression and how it was a desperate place, but much more than that, it was a sadness that I naturally incorporated into my identity over the years, into my personality and my writing. I have a heartbreaking reverence for humanity. This is how I survive. The manic part brought a lot of indecision, too, wasting time and moments that were precious over the years. And although it's something painful I’ve mined a lot from in my life, I will never forget those two months in the clinic or the people or characters that I met in the ward there, how all of that shaped my worldview and view of myself, much like this movie.

To this day, I take pills, blue and green like an ocean, usually in the mornings when the birds sing and the effect is an afterthought to the day. These days, I think about how we’re all going to die, that Robin Williams especially is dead, and so while I am alive, I should allow myself to understand and appreciate why that is. Where does sadness come from and how can I explore or navigate my own fruitfully now? I must express myself.

Whether it’s mental illness or counseling, Good Will Hunting connects us in very human ways to display what empathy can mean for a person or lifetime, especially my personal lifetime. I’m reminded of the scene towards the end with Will and Sean embracing in his office, Will breaking down in tears, Sean emphasizing, “It’s ok, it’s not your fault.”

If this film teaches us anything, it should be that none of us should have to be too strong for too long, that humanity is not an island, and that a lot of this life—a lot—is not your fault.

Thank you, Robin.

Christopher Bowen is the author of the chapbook We Were Giants; the novella When I Return to You, I Will Be Unfed; and the non-fiction book Debt. He was a semi-finalist in the 2017 Faulkner-Wisdom Novella Competition and an honorable mention in the 45th New Millennium Writing Awards in the non-fiction category.