vol. 22 - Everything Everywhere All at Once

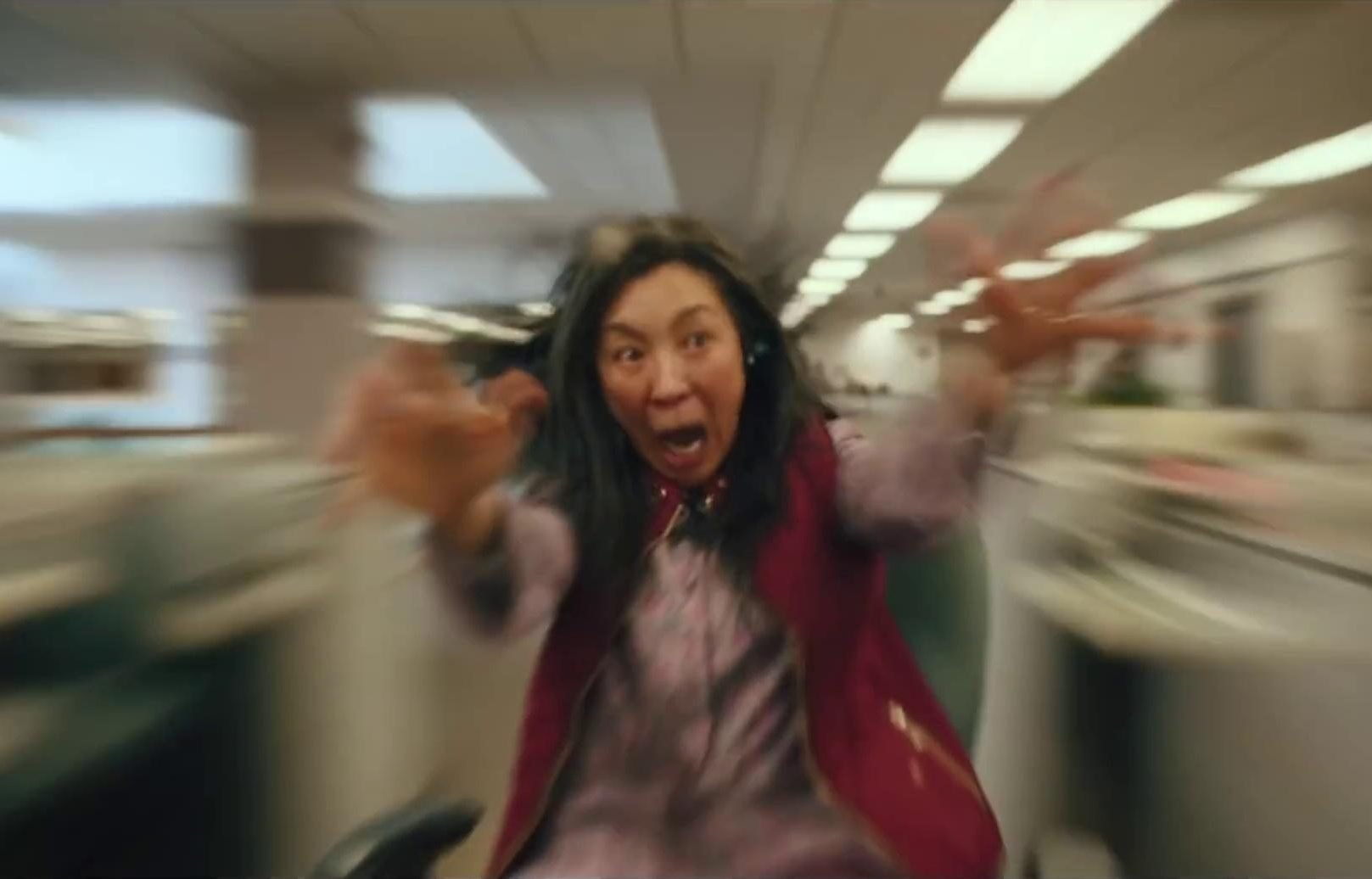

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

directed by Daniels

Amelia Akiko Frank

Everything Everywhere All at Once | 2022 | dir. Daniels

Everything

I don’t believe in a god, but if I did, it would be a god of wonderful minutiae. I don’t mean in the small-is-sublime way of Mary Oliver, but in the maddening way that the nodes of life can connect in pure coincidence. I got my second ever period in a middle school bathroom. I was unprepared, which could have been a mortifying disaster except for two factors. First, it was Halloween, and I was dressed as Boo from Monsters Inc.: my enormous pink shirt reached my knees and hid the red circle that had appeared in the crotch of my leggings. Second, my only friend happened to enter the next stall—I recognized her shoes—where there sat on the toilet paper dispenser an unopened sanitary pad, not only wrapped in plastic but also in a sealed box. This is a coming-of-age story.

My friend tossed the box over the stall door and for a pocket of time I was convinced about God. I opened my world to divine intervention: every lucky guess, each on-time train suggested something larger than myself at play. It seemed profoundly unlikely that something would just happen to work in my favor, or against it, or even in parallel; I was newly aware of the extraordinary scale of potential outcomes, and the absurdity of one event occurring instead of another. Later, in college, I would read Camus and find that my leap of faith was more like a lack of faith in the limits of possibility. Even later, this year, I would watch Everything Everywhere All at Once and find confirmed on the big screen the dazzling prospect that anything can happen anywhere, all at once.

Everything Everywhere All at Once explodes the premise of infinite possibility. The film imagines a multiverse in which characters can traverse parallel worlds (“verse-jump”) via unexpected, bizarre actions: chewing used gum, snorting a fly, slicing paper through the webbing between each finger. Paired with a high-tech earpiece, these unlikely maneuvers trigger a split-consciousness possession of an alternate-universe doppelgänger, allowing the verse-jumper access to the doppelgänger’s memories and skills. In other words, characters experience what could have been—what lives they might have led, expertise they might have had—if things were a bit different. But this access lasts only a moment. Anything longer, we learn, overwhelms the mind.

Protagonist Evelyn Quan Wang, played by the inimitable Michelle Yeoh, discovers that she is the most pathetic version of herself. Other versions of Evelyn are a famous singer, a martial artist, or the scientist who discovered verse-jumping in the first place (Alpha Evelyn in the Alphaverse). Meanwhile, our original Evelyn is the disastrous result of wrong turns and missed opportunities: her business is being audited by the IRS, her unhappy husband Waymond is attempting to serve her divorce papers, and her daughter Joy becomes increasingly estranged. As Alpha Waymond tactfully puts it: “You have so many goals you never finished. Dreams you never followed. You’re living your worst you.”

The prospect of living my worst me has always haunted me. Like Evelyn, I have had a great number of hobbies and tangential interests, and have, through the years, struggled to dedicate myself wholly to specific goals. In ninth grade, pursuing what I hoped was the most successful version of me, I transferred to an elite New York prep school.

Immediately, I recognized that everyone around me was somehow extraordinary, whether in terms of academic skill, extracurricular prowess, or fortunate birthright. Nobody was nobody, and the thing we all had in common was enormous potential. Potential unfurled before us like a carpet. Or, potential was fast-ripening figs, as in the famous passage from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar:

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

In the book, the protagonist Esther goes on to have a nice meal at a restaurant and feel much better. This is massively relatable. It’s true that a simple pleasure (a treat, I often say) can mollify an anxious internal monologue. I wonder, though, whether Esther’s treat would be enough now, when we can see everyone elses’ multitude of fresh figs on Instagram—when a new fig delicately blooms at the end of every minorly interesting Wikipedia article.

EEAAO can certainly be interpreted as a parable for the overwhelming, overlapping, interrupting, hyperlinked age of the Internet. Evelyn can access extraordinary skills by reaching across universes; we can access an inconceivable breadth of knowledge in a moment using Google. The world is much larger for us than it was for even our most recent ancestors. But it’s not just that information is too readily available, and the sheer amount of it explodes our human brains. I think, in large part, it’s that these massive reservoirs of content are so integrated in our lives that they become invisible. Getting stuck scrolling through an endless feed (paralleled in the film by the threat of getting sucked into an all-encompassing black-hole everything bagel) is not a neutral happening. I find that I often consider my mindless online time to be some kind of break, a moment away from the occurrences of the “real world” almost akin to rest—but even this time is an active choice; even this time is a fork in the road that is my life.

When Evelyn begins to verse-jump, Alpha Waymond warns her to return to her original consciousness as soon as she has acquired the necessary skills for the task at hand. Anything longer, we learn, overwhelms the mind. Extended verse-jumping is what triggers the central conflict of the film: Alpha Evelyn’s extensive verse-jumping experimentation on Jobu Tupaki, the Alpha version of Evelyn’s daughter Joy, destroys Jobu’s mind by allowing her to access all universes at once. It’s too much, and she becomes vengeful and destructive, realizing that nothing matters in a universe where every possible permutation exists. The problem isn’t that she knows too much, necessarily; it’s that each iteration of herself is equally real. She creates the all-encompassing black-hole everything bagel, an expression of her understandable nihilism.

In my case, I survived almost three years of pressure-cooker high school before my body gave out. My symptoms were chronic and vague: headaches, canker sores, urticaria, dizziness, nausea, memory loss, and a constant, heavy exhaustion. I often say that my senior year of high school was like walking through soup. Minor movements required enormous effort, and I was constantly aware of each part of my body. When I turned my head, I would say to myself, I am turning my head now. Taking notes in class, I would watch my own hand move slowly across the page as if it were some alien creature leaving a thin trail of loops and dashes.

I was trying to be every version of myself, and that was my great mistake. Like Jobu Tupaki staring into the bagel, like Esther watching the rotting figs, I was overwhelmed by everything, everywhere. I was eventually diagnosed with chronic fatigue, a vague moniker for my assemblage of symptoms, but I don’t think about diagnoses as much these days. We all know about burnout. I’m more interested in the things to which we hitch ourselves when the world and its choices become too much.

2. Everywhere

In September, I moved from Chicago to Brooklyn. I am trying to be an artist of some sort and New York (incidentally where I grew up) seems like the place to be. The move will be in some ways devastating: I am leaving a beautiful apartment, a meaningful teaching job, and some of my closest friends in pursuit of some abstract, cliché ideal of life as a creative in the Big Apple.

Much of my reasoning behind the move is that I need a change: Chicago has become, for me, the city of college and Covid, and I feel that I need a fresh start decidedly away from campus and quarantine. I am also trying to lean into decision-making. Like Esther under the fig tree, I am prone to unhelpful waffling and wavering.

As I navigated Chicago Midway Airport—one of my least favorite places in the world, along with most other airports—with my cat in her carrier, I found myself thinking about two anecdotes my dad had told me as a child. The first was the right-hand rule: when I first read D'Aulaires' Greek Myths in third grade or so, my dad mentioned off hand that if Daedalus’s labyrinth were a true labyrinth (that is, having no branches, unlike a maze), the Minotaur should have been able to quickly find the exit by keeping his right hand on the wall at all times. The second anecdote was about Schrödinger’s cat. I remember standing on a subway platform, nine or ten years old, as my dad tried to explain how quantum physics meant the cat was both dead and alive. I was extremely upset about the possibility of the cat being dead, and not especially comforted by the prospect of the cat being alive.

I have often felt like some combination of the Minotaur and the cat: confined in an ambiguous half-life in my indecision and fear. I don’t think this is especially uncommon. I’ve spoken to friends about how difficult it is to even commit to reading an entire book these days. Knowing how much there is out there to learn, to read, to see, it feels futile to pick what specific thing is worth my attention at any given moment. Also, in recent years, the world has felt increasingly terrible. How can I focus on anything as the death counts and oceans continuously rise?

During my two years of teaching at a K-8th school, I saw my own general disillusionment mirrored in many of my students. They were bright, creative, and often pessimistic. They were also content fiends—with a few exceptions, my students turned to digital media for comfort and distraction. There were two media phenomena they were especially excited about: “shifting,” a lucid dream-esque method of transcending into your “desired reality” popular on TikTok, and the Marvel multiverse.

There's something to be said about the state of the world when children emphasize the possibility of alternate versions of reality. It seems there’s been an explosion of multiverse media recently, for both children and adults: shifting and Marvel, of course, but also Rick and Morty, The Umbrella Academy, Russian Doll, Shining Girls, Into the Spider-verse, Riverdale, even the idea of “alternative facts.” Notably, these examples don’t just propose fantasy communities hidden within our world, like the Harry Potter or Percy Jackson series. Rather, they suggest that infinite universes branch off from ours—some that look very much like home, and some that would be entirely foreign. And each universe is real to the billions living within it.

It makes sense to turn to the multiverse when living in our universe feels very bad. The multiverse says: even if your version of things is awful, even if you are an utter failure, there is another version of you that excels. There is another version of the world that has put an end to climate change and inequality and war. Our original Evelyn is special, as Alpha Waymond puts it, because of her proximity to other universes via her many abandoned goals and dreams.

This faith in something greater outside of our lived experience is a religious belief. The notion that our shortcomings might be expunged in another world leans Christian. Faith can be a beautiful thing (although Camus, I learned in college, calls religious hope the greatest evil), but I don’t believe in a god. To what can I hitch my life—my sense of meaning—if not to the promise of a better version of me?

The successful CEO version of Waymond has one of the most poignant, and oft-quoted, lines in the movie; speaking to the movie star version of Evelyn after her premiere, he tells her, “I wanted to say, in another life, I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you.” Even in his success, there’s something missing. In everything, there is a hole, an exception. That’s where I hitch myself—to the belief that nothing is absolute. That even if there were another version of me who had the perfect job, or a million dollars, or a superpower, that version is missing something too.

So here’s what I love about EEAAO: our protagonists are emphatically not in the Alphaverse, and it’s wonderful. Kind, sensitive Waymond does not undergo a macho transformation into an Alpha male. In fact, despite their technological advancement, all of the Alpha characters die. In fact, they die because of it. In their final moments, did they wonder: is there a version of me out there who lives another fifty years?

3. All at Once

I don’t believe in a god, but if I did, there would be many gods. Their realms overlap; each creates its own little ecosystem, maybe even its own parallel world. I’m aware of only a minute percentage of the total cosmology. This is a coming-of-age story. There is no perfect thing—only wonder at the nodes of coincidence.

Amelia Akiko Frank is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn. Her work has been shown at Logan Center Gallery, Tutu Gallery, and the New York Academy of Art, and featured in publications including Right Hand Pointing, *82 Review, and Working Document. She likes survival stories, cardamom, and making noises. Say hello: ameliafrank.art or on Instagram @a.kitsu.