vol. 20 - One False Move

One False Move (1992)

directed by Carl Franklin

Dalton Huerkamp

One False Move | 1992 | dir. Carl Franklin

There’s a quote (I believe from John Waters) that has vexed me for some time: “America would be a much more interesting place if people lived in their hometowns.” Is America uninteresting? In some respects, I think America may be a bit too thought-provoking. But the assumed symptom is that old boilerplate: “There lies the Radiated Lands, where from the Thought Leaders flee...” (Also, not everyone’s hometown is Baltimore, a town interesting enough to birth Animal Collective and kill Edgar Allen Poe.) Yet the core of the quote, a responsibility to where you come from, has occupied conversations with friends and (ultimately) clouded considerations of occupation.

In August of 2020, I moved from Northwest Arkansas to Northeast Arkansas for a job. Following safely behind a U-Haul, I saw the landscape shift from the rolling woodlands abutting I-49 to the chessboard planescape divided by US-49. Ah, the Radiated Lands. It felt like driving a hot iron across a wrinkled shirt. For both activities (driving or ironing) I’m usually listening to a film podcast, or thinking about that darn quote.

Neither corner of the state is my hometown per se; I grew up in what Charles Portis dubbed “Ark-La-Tex.” [I blame Portis for my bias against Texans (see LaBeouf in True Grit), as well as one of the colleges in my hometown (a school for future LaBeoufs).] The landscape is different, too. Shaggy pines tower where Caddo land hasn’t been grazed for gas stations or dorms. Some pines are haunted by elder oaks, guarded from razing by creek beds or general isolation. Without the majestic waves or existential vastness, it’s a land only Charles B. Pierce could love.

The nearest movie theater from my hometown was forty-five minutes away, in the town where they filmed Slingblade. Growing up, I didn’t seek out films filmed in Arkansas like Slingblade, or David Gordon Green’s George Washington. I was a little green with envy at 12 or 13 that someone up and filmed something there instead of Here. I also feared the film would say something negative about the state I thought only I could think. If any, I stuck with Arkansas films set in the past or steeped in genre: True Grit, A Face in the Crowd, The Town That Dreaded Sundown and (later) Ride a Crooked Trail.

Thankfully, there was a movie theater a block away from my new apartment. But I didn’t know that I would be living right across train tracks. The Northeast ended up being much more…agrarian. Boxcars full of rice and grain roistered outside my window at 2 am. I walked from car to office before dawn, office to car after sunset. I’d occasionally fall asleep during a Tuesday matinee. On my lunch break, I read Rovers by Richard Lange, wherein (spoilers) a vampire dies after being cornered in a roadside field without cover or shade. It hit a bit too close to home.

In an unfamiliar environ, I found cover with familiar, cinematic exploration. According to my Letterboxd diary, I watched one hundred and forty five movies between last July 19th and December 31st, with only two rewatches (one was The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, a Halloween tradition). Between the early variants and Omicron, some of these watches were in the electric seat of the neighborhood theater. Most were in the at-home easy chair through TCM. I poured over the monthly schedule, jotting down long sought-after titles in my agenda.

During this ongoing period of voracious viewing, I saw One False Move for the first time. I first heard of One False Move from William Boyle, who tweeted about the film popping up on TCM. Boyle is part of a group of Oxford writers like Megan Abbott, Jack Pendarvis, and Ace Atkins who all confirm that you can both 1) love writing books, 2) also love movies, and 3) the love of the latter does not diminish the love of the former. Each writer has their particular film niche (e.g., Pendarvis loves Jerry Lewis), and Boyle, a crime writer, has great taste in crime films, particularly ‘90s neo-noir.

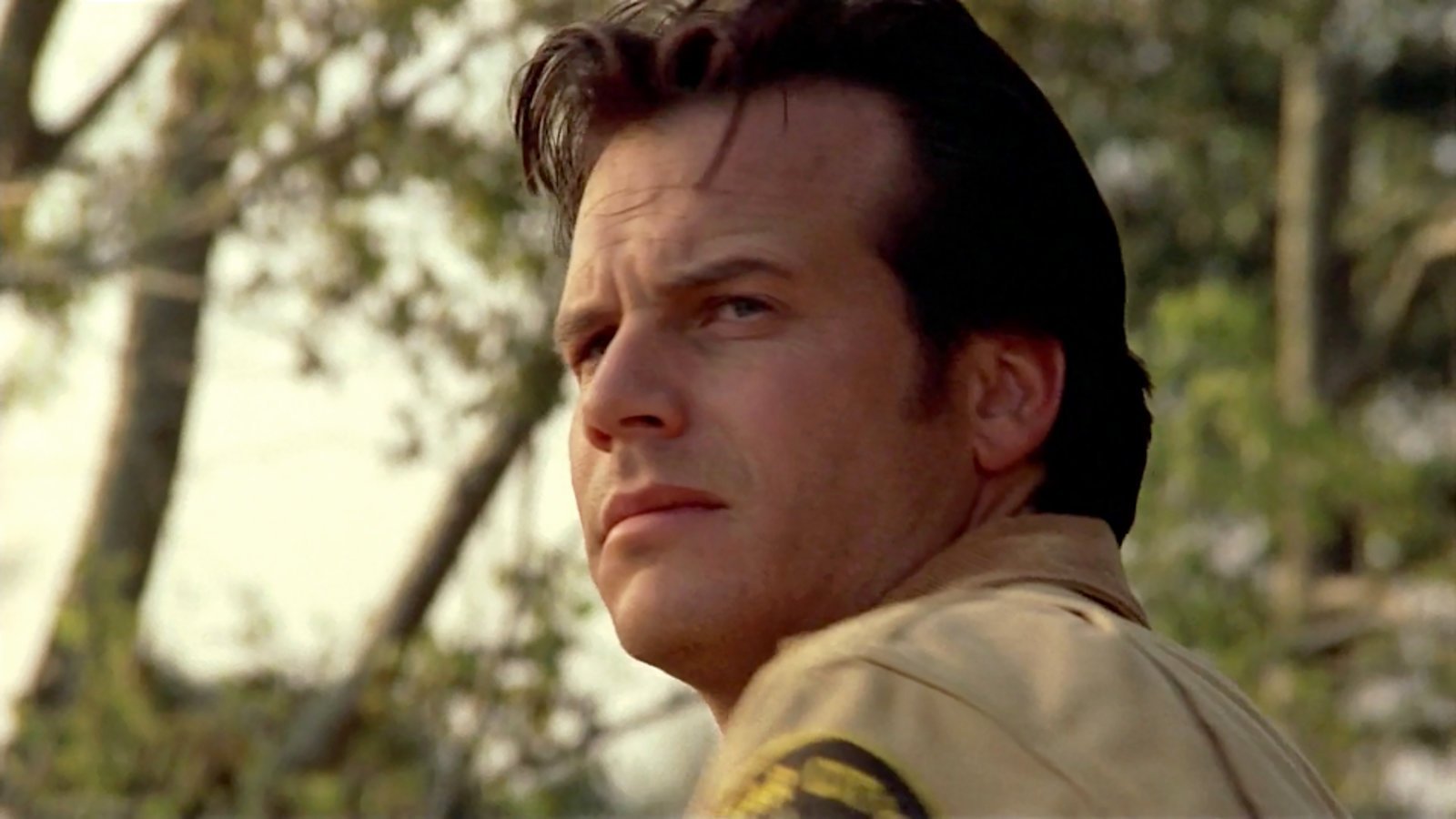

One False Move centers on two criminals: Dale “Hurricane” Hudson and Fantasia. Hurricane (Bill Paxton) is the Chief of Police of his hometown of Star City, Arkansas. In the tradition of Scream’s Deputy Dewey and the aforementioned Barney Fife, Hurricane is, on the surface, an ignoramus. We see his giddiness on a conference call with the LAPD, his boastfulness while giving a town tour, his brashness while handling a domestic disturbance. We later learn Hurricane raised a family at the scene of his crime.

We aren’t told what Fantasia (Cynda Williams) does in Hollywood (technically L.A., but I’m taking an article liberty). When we meet her in the film’s opening, she’s literally opening a door. Like the criminal role of a getaway driver or lookout, she participates, without “active” involvement, in what becomes a truly horrific crime. I say “horrific” without hyperbole; it’s up there with the pool scene in Burnt Offerings. Fleeing while the bodies are still warm, Fantasia does what she told one of the victims at the door: she’s going to Star City. Tonight. And “Star City’ doesn’t sound too far off from a corny name for Hollywood.

Despite giving away the ending of Rovers above, I’ll avoid discussing the connection between Hurricane and Fantasia. I will say it’s the sort of reveal that necessitates a rewatch, and I plan to do so once Kino Lorber releases its Blu-ray of the movie. And this secret casts a more sinister light over what appears to be a bare-bones crime story. I prefer the alternate tagline for this reason: “Nothing is as dangerous as the past.”

The film’s main tagline is this: “There was no crime in Star City, Arkansas. No murder. And no fear. Until now.” As great as that tagline looks spaced out on a poster, it’s a lie. As mentioned, we see a domestic disturbance while on a ridealong with Hurricane. Unlike the housebound L.A. crime, the Star City scene spills out into the street, as does the climatic collision. That seems to be the only distinguishing feature between Hollywood and Star City. Even the little white houses look the same, set back from the road and holding some sinister air.

What struck me on first watch was how instructive the film was. Setting aside the socio-political discussion, hillbilly media going back to the ‘60s presented such morality tales. I recall a men’s Bible study at my hometown church that paired verses with an episode of the Andy Griffith Show. We rarely get such life lessons from contemporary film. Maybe “don’t live in a lighthouse with Willem Dafoe”? And, sadly, the warning of most crime genre exercises mirrors Proverbs: women are fatale.

One False Move, instead of assigning blame, presents the outcome of two choices: Hurricane stayed in his hometown while Fantasia left. Two roads diverged in an Ozark wood… This has been a conundrum since the fundamental right to travel. And it will remain one likely until climate disaster makes fleeing the Radiated Lands refugees of us all.

No matter where they live, humans, by the mere act of living, graft stories onto the landscapes. And all these stories are quote-unquote interesting. As interesting as watching a face on a screen. As interesting as reading the thoughts of some distant narrator from a page. I’m thankful One False Move doesn’t try to answer the question posed by (possibly) John Waters. Because the filmmakers don’t have the answer; neither do I. For now, it is enough for the work to engage in a collective pondering.

But here is one certainty: Stay or go, eventually you will come back.

Dalton Huerkamp is a writer and attorney from Arkansas. His works have appeared in Dinner Bell, Black Moon Magazine, Entropy and the Shut Down Strangers anthology from Bone & Ink Press. He currently resides near Memphis with his cat, Lydia.