vol. 12 - Girlfriends

Girlfriends (1978)

directed by Claudia Weill

Zan McQuade

Girlfriends | 1978 | dir. Claudia Weill

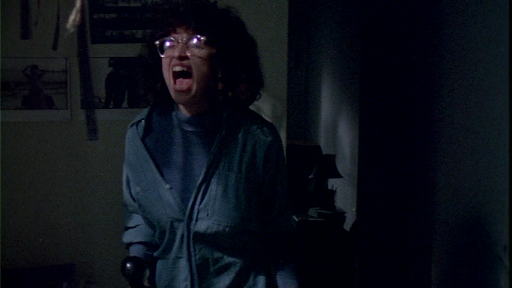

We begin with the view of a woman’s shoulder, wrapped in darkness. We hear the click of a shutter capturing her silhouette, and then two female voices in the dark. “Did you dream again? Did you have a bad dream?” one asks the other. Two women, intimate enough to know each other’s dreams, the good and the bad.

Girlfriends is Claudia Weill’s feature directorial debut, written with Vicki Polon and starring Melanie Mayron as Susan Weinblatt, a photographer seeking social and professional independence in 1970s New York City. The film recently became popular again for its influence on other notable pieces of young, female art: Lena Dunham cited it as an inspiration for Girls, and Greta Gerwig paid tribute to Girlfriends through both plot and theme in her film (co-written with Noah Baumbach) Frances Ha. At the prime age of 43, Girlfriends is either shockingly modern, or the female struggle for independence and recognition since the 1970s has been disappointingly stagnant. Either way, what draws me most to Girlfriends is the fact that it centers the story on women in general, and on female friendship in particular—in a way that reminds me how few pieces of art ever really do this.

Men, of course, play a role too: early in the film, Susan’s best friend Anne (Anita Skinner) goes off to marry Martin (Bob Balaban). (Susan: “You were the one who left me.” Anne: “I didn’t leave you; I got married.”) Susan then ends up in a small series of relationships with men—Eric (Christopher Guest), who she meets at a party and has a brief fling with, and Rabbi Gold (Eli Wallach), the rabbi she works for photographing bar mitzvahs and weddings. Both relationships end quickly: with the rabbi, after she meets his wife and son; with Eric, twice, as his behavior (stealing all the blankets, keeping his ex-girlfriend’s paintings hung in his place, not using yoghurt in his mashed potatoes) makes her realize she prefers a room of her own.

But Susan’s relationship with women (and more specifically, with her own career as a woman) are at the true heart of the film. Susan’s friendship with Anne is its dominant tension, the bass note. (Eric: “So why did you leave?” Susan: “I was just coming out of a heavy relationship.” Eric: “You were living together?” Susan: “Mm-hmm.”)

Susan also forms a relationship with a hitchhiker, Ceil, a young dancer who ends up crashing at Susan’s apartment and even briefly coming on to Susan, before Susan decides she’d be happier once again having the space to herself. Other key female relationships define Susan’s rise to independence: Julie, a fellow photographer, offers Susan the chance to work as her assistant, before Susan returns the favor by recommending her to a gallerist. The female gallerist, too, plays a pivotal role: she is the one who both enables and announces Susan’s arrival in her career.

Weill has always centered the lives of women in her films, even in her background as a documentarian; her previous films included Joyce at 34, about women balancing career and family, and The Other Half of the Sky: A China Memoir, about a women’s group headed by Shirley MacLaine visiting China to witness the lives of liberated Chinese women. After Girlfriends, Weill directed a second feature, It’s My Turn, starring Jill Clayburgh as a mathematician whose “the woman who has everything” life becomes complicated when she meets and falls in love with an ex-baseball player, played by Michael Douglas. (It’s My Turn, incidentally, was written by Eleanor Bergstein; in multiple interviews, Weill cites a line from Bergstein’s Advancing Paul Newman [“This is a story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection with life”] as the inspiration for Girlfriends. Bergstein would also later go on to write another film centering a young woman trying to define the parameters of her independence: Dirty Dancing.)

Girlfriends is not just about centering any women, but the kinds of women Weill wanted to see more of in film. Weill had originally received a grant to make a documentary film about being a Jewish woman in America, but the film transitioned into Susan’s story. (Which is, of course, still about being a Jewish woman in America; Susan confesses to Rabbi Gold that she once wanted to become a rabbi so that she could have her own conversation with God. At the time the film was made, female rabbis were a relatively new phenomenon; Sally Priesand, the first American female rabbi, was ordained only in 1972.)

Here’s Weill describing why she made a film about a protagonist like Susan in an interview at the UCLA Film and TV Archive in 2017: “I was very interested in having a protagonist who was not the traditional protagonist. I guess it’s self-defense, or something. My grandmother, when she saw a cut of the film, she said ‘Why did you follow the vulgar girl who speaks with her hands? Why didn’t you follow the blonde girl?’ That’s why I made the film.”

In a review of the film in Film Quarterly in 1978, Marsha Kinder describes Susan as “an intelligent, talented, warm, generous, humorous, courageous, vulnerable young woman who grows confident of her work and independence. […] She is not just a ‘creative person’ with lots of potential, but a serious working photographer who develops her talents.” Kinder then goes on to contrast this with Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman, which starred Jill Clayburgh a few years before her role in Weill’s It’s My Turn: “both films focus on a heroine who gains confidence in living alone after being rejected by a roommate.”

Susan’s resistance to being either rejected or edited—when a magazine editor crops her photograph of Anne (“I thought the blonde in the bed needed reframing”), she no longer considers it her own—is what defines her. This is a constant in the lives of most women I know: being defined by others, refusing it, fighting against it, and in the fight, becoming ourselves.

“The film is autobiographical—emotionally,” says Weill in the UCLA interview. Women are often accused of making overtly autobiographical fiction, but here Weill makes a key distinction between how women’s fiction is viewed by others and how it really is: it’s about her, but it’s not her. This can be a difficult distinction for many to grasp, how women are able to place themselves in a story without making the story exactly or necessarily about them.

Weill simply picks up a thread in a woman’s life and follows it, acknowledging that there are as many threads in the world as there are women. The biographical aspects of the story could just as well be about Melanie Mayron, who went on to be better known for her role as another photographer, Melissa Steadman in thirtysomething (a few episodes of which Weill also directed), as well as taking her own turn directing shows such as GLOW (Susan practically predicts this herself when she says to Rabbi Gold “my grandfather loved lady wrestlers”) and the modern reboot of Dynasty. Mayron played similarly quirky characters in two films made just before Girlfriends: Car Wash and Harry and Tonto (again, Mazursky). But to even try to say that these films are about specific women denies the fact that these are films about a variety of women: about how these women are similar, and how they are different.

Weill uses the color red to visually center the variety of experiences in the lives of Susan and the women around her: the wall of Susan’s apartment she paints after Anne’s wedding, the poorly fitted caftan Anne brings Susan from her honeymoon, the red outfit Julie wears while telling Susan of the joys of post-divorce independent living, Ceil’s red scarf she wears as she hitchhikes by the side of the road, the red ribbon on a celebratory bottle of tequila and the red crushed velvet dress Susan wears the night of her gallery opening, even the red of Susan’s skirt the night she and the rabbi share an intimate moment.

At Anne’s house, on the other hand, red is used to highlight her domestic burdens (“Do you know that I haven’t been alone more than ten minutes of my life?”)—the color of the basket full of children’s toys, a child’s automatic swing chair, the red of her daughter’s Raggedy Anne doll hair—as well as a glaring reminder of the life of a poet she left to become a mother, represented by the bright red “Enter” key on her typewriter.

Red, finally, is the color of the crumpled flannel robe on Anne’s bed just before she tells Susan she had an abortion that morning.

Girlfriends dared to remove the lens from the men and refocus it on the women and their relationships from its very opening scene. This can throw those who aren’t used to seeing women’s lives centered. In the introduction to his 1980 interview with Weill in Film Comment prior to the release of Weill’s second feature film, Brooks Riley offers an assessment of Weill’s art that misses the point of it entirely: “One weakness she shares with other women directors is a tendency to lavish that complex characterization on the female protagonist, leaving the men as ill-defined drones to serve the quixotic destiny of a queen.”

To be accused of not developing the male characters in a story where women are centered is a deeply aggravating misunderstanding of how men, believe it or not, can indeed be secondary to women’s stories. Centering women in art affords us such epiphanies.

Anne: I can see you really take me seriously.

Susan: I take you more seriously than you take yourself.

Independence for Susan comes down to centering herself: in her own place, in her own gallery show, in her own body, in her own conversation with God. During an argument with Eric, Susan proclaims that “I like me when I don’t need you.” It is an incredible line, a very 1970s second wave feminist sentiment that defines female independence at its purest. We don’t need men to become ourselves.

The shots in Girlfriends that stick with me the most are the shots of Susan alone. Susan alone at a party, Susan in her apartment alone, Susan walking the streets of NYC alone.

Even when there is a tinge of sadness to these moments, the sadness is just the sound of the chrysalis cracking. It is in these moments—alone, centered—that Susan becomes herself.

Zan McQuade is an editor, writer, photographer, translator, and baseball enthusiast living in Cincinnati.